Aside from the predefined commands in the PlotDevice reference you can also define your own custom commands. Creating a command is a design strategy in which you re-use certain actions or pieces of your script.

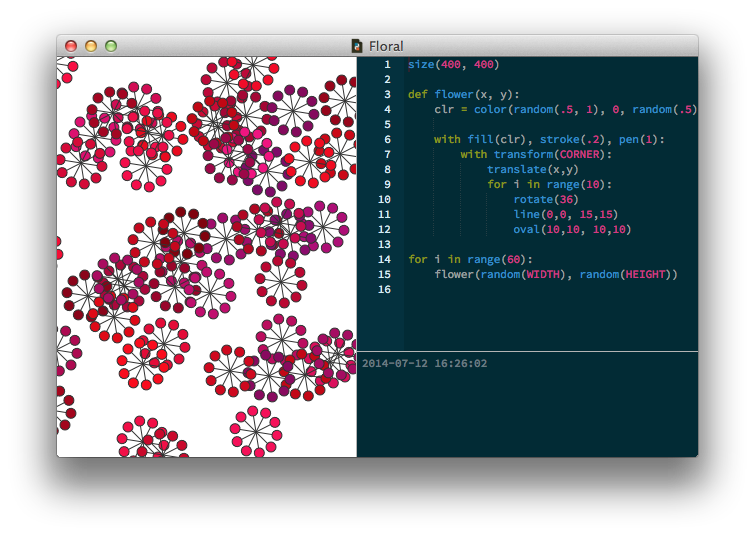

For example, in the above example all the actions to draw a flower (ten red-pinkish ovals connected by lines) are grouped in a handy flower() command. The ‘recipe’ for drawing a flower only need to be defined once, then we can use it to create one flower or an arbitrary number of them. It also means that we can modify the code in a single location and have its affects apply to the entire script.

Defining your own commands is like loading up a toolbox with the perfect set of tools for the project at hand.

Command definition

As a simple example let’s define a header() command that draws a piece of text and applies some standardized styling attributes:

def header(txt, x, y): fill("red") font("Helvetica", "bold", 12) text(txt, x, y)

The definition of a command starts with def, followed by the name of the command and a (parenthesized) list of parameters. Don’t forget the colon at the end of the line – this tells PlotDevice that the intented statements below are what the command does.

Though you can name commands any way you want, Python has some conventions that will make it easier for others to understand your code:

- Use a simple and relevant word that describes what the command does.

- Use lower case and separate words

with_underscores(camelCaseis so Java...). - Commands that return

TrueorFalseshould start with ‘is’:is_white,is_alive,is_big, etc. - Commands that change and return a value should use a verb:

adjust_contrast,strip_tags,reticulate_splines, etc.

Parameters

Command definitions don’t ‘do’ anything in and of themselves. Instead, you’re teaching PlotDevice something – for example, what a ‘header’ is. The commands you define need to be called from somewhere else in the script. This is where parameters come in: notice how the definition of header() uses a txt, an x, and a y parameter. These are used like variables inside the definition.

When calling the command, you supply real values for txt, x and y:

header("Templating", 20, 40)

PlotDevice would now execute all of the code in the header() definition, with txt being ‘Templating’, x being 20, and y being 40.

Return value

You may have noticed that some commands in PlotDevice ‘return’ a value that you can store in a variable. For example, measure(txt, width) returns the dimensions of a paragraph displaying txt with a column size of width (typeset in the current font()).

def paragraph(txt, x, y, w): fill(0.2) font("Baskerville", 16) text(txt, x, y, w) col_w, col_h = measure(txt, w) return col_h

The return statement selects the value that will be passed back to the caller. This can be any datatype: a number, a string, a list, or even an object. The return statement also signals an immediate end to the command. It should almost always be the last line in a definition (since anything below it will never be reached).

Example

To see how moving repeated operations into their own commands can simplify your code, consider the (somewhat contrived) example of laying out boxes of differently-styled text. Let’s first look at how you would do this the ‘naïve’ way, using top-to-bottom logic and (re)defining the styles before every line of text is drawn:

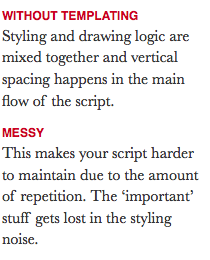

x, y = 20, 30 w = 200 fill("#c02") font("Helvetica", "bold", 12) txt = "Without templating" t = text(txt.upper(), x, y) y += measure(t).height + 4 fill(0.2) font("Baskerville", "regular", 16) txt = "Styling and drawing logic..." t = text(txt, x, y, w) y += measure(t).height + 10 fill("#c02") font("Helvetica", "bold", 12) txt = "Messy" t = text(txt.upper(), x, y) y += measure(t).height + 4 fill(0.2) font("Baskerville", "regular", 16) txt = "This makes your script harder to..." text(txt, x, y, w)

That’s a lot of repetition even with only four text blocks, but imagine if it were drawing not two but twenty paragraphs. Then you’d have to define fonts and colors over and over again, and probably end up feeling like a robot trying to explain something to another robot.

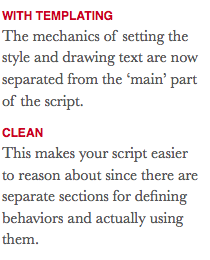

The nicer alternative is to ‘factor out’ the repetitive bits into a command to draw headings and another to draw paragraphs. We can define these commands at the top of the script and then use them below:

def header(txt, x, y): font("Helvetica", "bold", 12) t = text(txt.upper(), x, y, fill='#c02') return measure(t).height + 4 def paragraph(txt, x, y, w=200): font("Baskerville", "regular", 16) t = text(txt, x, y, w, fill=.2) return measure(t).height + 10 x, y = 20, 30 y += header("With templating", x, y) y += paragraph("The mechanics of setting...", x, y) y += header("Clean", x, y) paragraph("This makes your script easier...", x, y)

In addition to shortening the code a bit, you’ll notice that the ‘flow’ of our script now consists entirely of defining the headers and paragraphs we want to draw – all the styling has been abstracted away by the commands. This makes it easier to figure out what’s going on when you return to a script you wrote weeks or months ago. It also simplifies the process of tweaking the style since you can change the color or font of all the headings by changing a single line in header() rather than requiring an error-prone search-and-replace across the whole script.